POWELL RIVER – Two decades of farming on the Sunshine Coast could be nearing their end for a Powell River couple following the Agricultural Land Commission’s rejection of proposals aimed at diversifying their operation.

“It’s not easy. With the cost of everything going up, most farmers are starting to go, ‘hey, we’ve got to diversify,’” says Debbie Duyvesteyn, who with her husband Roger operates Coast Berry Co. Ltd. in Powell River.

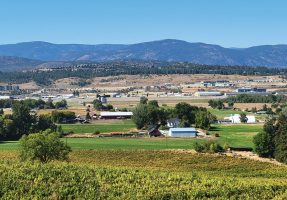

The couple established the farm in 2006, transforming the 43-acre property into a productive strawberry and blueberry operation engaged in direct sales and packing berries for sale at grocery stores south to Gibsons.

“We built a processing plant,” she said. “[But] the farm’s not making enough money to sustain it all.”

The past couple of years have been particularly hard.

The cost of strawberry plants rose to 60 cents from 13 cents, while the soil used in the farm’s raised-gutter production system tripled in cost.

“That soil has to be replaced every three years, due to a lack of nutrients,” Duyvesteyn says. “Last year and this year, we only planted half the field of strawberries because we couldn’t afford the soil.”

Yields have also been lower, due in part to weather, and it’s been tough to raise prices even on farmers market sales given the price-sensitivity of consumers.

“We didn’t raise the price too much last year; we put less berries in the containers to try to offset the cost (shrinkflation), which a lot of people did. And you barely cover the cost,” she says.

The result was an underwhelming income that prompted them to consider hiving off a 10-acre portion of their property for sale to others, potentially a family that wanted to establish a market garden. Application was made to the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC) last year, and a decision was handed down in December.

“We’re never going to farm over there; we can barely manage what we’ve got over here,” Duyvesteyn says. “But [the ALC] came back and said no, because it would give us opportunity to have more housing on the land and take away from valuable farmland.”

The couple then drafted a proposal for an agri-tourism operation, including 10 RV pads for seasonal accommodation. But in order to proceed, they needed a permit to bring in gravel.

“We already have approval to do septic and get a driveway put in, but the rules on ALR land are, if you want to bring one ounce of fill or gravel in or out of your farm, you need to have permission from the ALC,” she says. “And we were rejected.”

While the local farmers institute opposed the subdivision application on the grounds that it would open the door to housing on farmland, qathet Regional District endorsed the agri-tourism plans. Duyvesteyn says the ALC never provided a clear explanation for its rejection of seasonal accommodation.

“I said, ‘What box is it that we’re not ticking?’” she recalls. “[The planner] couldn’t tell me. … They told me, ‘Apply for a non-farm use.’”

The rejection was especially frustrating because a property across the road from Coast Berry continues to receive loads of fill three years after the ALC issued a stop-work order.

Powell River is also home to year-round RV parks, a boat repair business and other ventures not engaged in agricultural production.

“How come no one’s inspecting all this protected farmland?” she asks. “Then you have people like us that are farming at a fairly decent rate and we ask to have a little bit of gravel on here to extend the farming business and they say ‘no.’ … We should have just gone and done it. We probably would have gotten away with it. How would anybody know?”

Underfunded, understaffed

ALC staff told her the pressure on their resources have been ongoing for the past three years, a point agriculture minister Lana Popham acknowledged when MLAs reviewed her ministry’s budget in the legislature earlier this year.

Nominal increases over the past five years have given the ALC an annual budget of $5.5 million this year, up from $4.9 million in 2020 – an increase that’s lagged inflation, even as demands on enforcement staff have increased.

With more people working from home during the pandemic, more eyes were on farm properties, meaning more issues came to the fore. Many people also saw opportunities to start home-based businesses, while cost pressures saw farmers look for ways to add income streams.

This has resulted in increases in fill deliveries as well as agri-tourism ventures that aren’t fully compliant with existing regulations. These contributed to 1,049 active investigations at

March 31, up 13% from a year earlier.

“The average workload per officer is now 171 files for each of the six officers and continues to grow,” said ALC operations director Avtar Sundher.

Several farmland owners have established event venues both in the Lower Mainland and less populated areas to capitalize on the appeal of a country setting.

Delta, for example, is taking a closer look at applications for new construction on farmland after the discovery that some structures that received approval as farm buildings were hosting events and providing accommodation.

While diversification of on-farm revenue was envisioned as part of provisions allowing for additional dwelling units on farms under rules that came into effect in 2022, the rules still need to be followed.

This is what frustrates the Duyvesteyns, who sought to follow the rules and have no desire to sidestep due process at this point. Doing so would be in direct contravention of ALC decisions, potentially complicating any future application.

But the frustrations have robbed them of any immediate desire to submit further applications, especially if there’s no guarantee of success. Instead, they plan to sit tight and bide their time.

Duyvesteyn’s husband is a fifth-generation farmer whose parents emigrated from Holland in the 1970s and established a thriving greenhouse in the Lower Mainland. Challenges aren’t unknown, but the restrictions on diversification present a near-existential challenge to them.

“We’re telling our kids, ‘Don’t be involved. Go get careers outside the farm because it’s not going to work,’” Duyvesteyn says. “You can’t just keep getting deeper and deeper into debt.”

Squeezed by production costs and without alternative sources of income, the Duyvesteyns find themselves quite literally at a loss. The only consolation is that they’re not the only farmers in BC facing tough choices.

“We don’t really want to stop. We love what we do. But we have to live,” she says. “I know we can’t be the only farmers going through this with the ALC.”

Showdown looms over co-op’s surplus

Showdown looms over co-op’s surplus